Here's why UX Writing is so important

There’s lots of talk about UX Writing and hiring writers to help design copy for your product, but what does that actually mean? And how is it different from working with a copywriter?

UX Copy is a hyper-focused discipline within the world of writing: it’s about crafting the voice your product projects into the world, and understanding how others interpret that. The UX writer distills that knowledge into a voice, and creates a repeatable system for the way your product speaks to users.

As a result, UX writing often sits somewhere within the design organization of your business, as a part of the design process before a product is built. That’s intentional, ensuring your product is able to speak to users effectively.

There’s a lot of ways UX writing is great for business, so I thought I’d share what it’s like to work with a UX writer from my own perspective, and how UX writing can help your business.

Seeing through your user’s eyes

You’re probably accustomed to working with copywriters, but there’s a big difference when it comes to the world of UX writers: it’s less about flashy copy, catchy sentences and cute wording.

UX Writing is about considering the overall flow and implementation of a design, and how it guides a user through it. It isn’t about giving the user cute error messages like “oh no, something went wrong,” but is focused on providing them with a clear path forward through the use of copy.

A good example of this from my previous work is a client that wanted help with the onboarding flow, as users were falling off along the way, without completing it. After taking stock of all the strings in the flow, it became apparent that the action button designed to push the user forward was changing on every step: sometimes it might say “Get my API key” and other times it said “Next.”

For users, this was confusing. Not because they were stupid, or unable to understand how to move forward, but that they actually didn’t want to complete the task the button implied much of the time. Putting a blocking step that says “Get my API key” when a non-technical user signed up meant they figured it was the wrong place, and started trying to exit the flow.

This is called ‘moving the cheese’ which alludes to a mouse trying to get to where it wants to be, but the final destination seemingly not on the horizon. We made a number of changes to the flow, including the use of titles and descriptions to help the user understand if they needed to do something, and most importantly, a consistent way to move forward.

If you’re building an onboarding flow, or helping your users for the first time, copy is one of the most important tools you have to help people with difficult to understand concepts. Looking at it from their perspective (and in many cases, identifying what type of users are the audience), then guiding them forward so that it’s always clear what’s next is key.

Understanding the technical details

UX Writing can do a lot of heavy lifting for you, if your writers understand what’s going on and are able to help translate that for the user. As a writer with a technical background, I’m allergic to jargon like ‘authentication error’ or ‘gateway unavailable,’ because it means nothing to your users!

The job of a UX writer is making it incredibly clear to the user what’s happening both when something in your app goes right and when it goes wrong. A good UX writer should understand the technical details of what’s happening, and translate this into something coherent, simple and actionable for the user so that they always have a way out of a dead end.

Here’s a practical, fabricated example I often see around the web:

Authentication error: [523] Unable to access this system.

I hate these errors, because they’re written by developers, and I can’t even understand what’s wrong here. Did I do something wrong when trying to log in? Is the system down? Do I not have adequate rights to log in?

In projects I’ve worked on previously, I try to understand all of the error states we might end up with and work them into specific, cruft-free messages that lead the user to understand what to do next. We could take the above error and transform it into different error states, depending on what went wrong:

In the case of the user typing a wrong email or password:

Sorry, your account details were incorrect. Reset password here if you're stuck.

In the case of the server having unknown technical problems:

Our services are unavailable right now, so we can't log you in. Try again soon.

And, one last unique message, in case a user’s account isn’t actually allowed to do that:

Your account needs permission to access this area. Click here to message the team owner for help.

All of these messages tell the user precisely what went wrong, why, and don’t leave them hanging wondering what’s next.

Concise text always wins

When developers are left to fill in text in an application, they tend to do so by being overly verbose, or adding way too much text that adds little value to the message.

In the fantastic book On Writing Well by William Knowlton Zinsser, he says that “the secret of good writing is to strip every sentence to its cleanest components.” You should seek to do the same across your product, because it offers a refreshing change of pace: getting directly to the point.

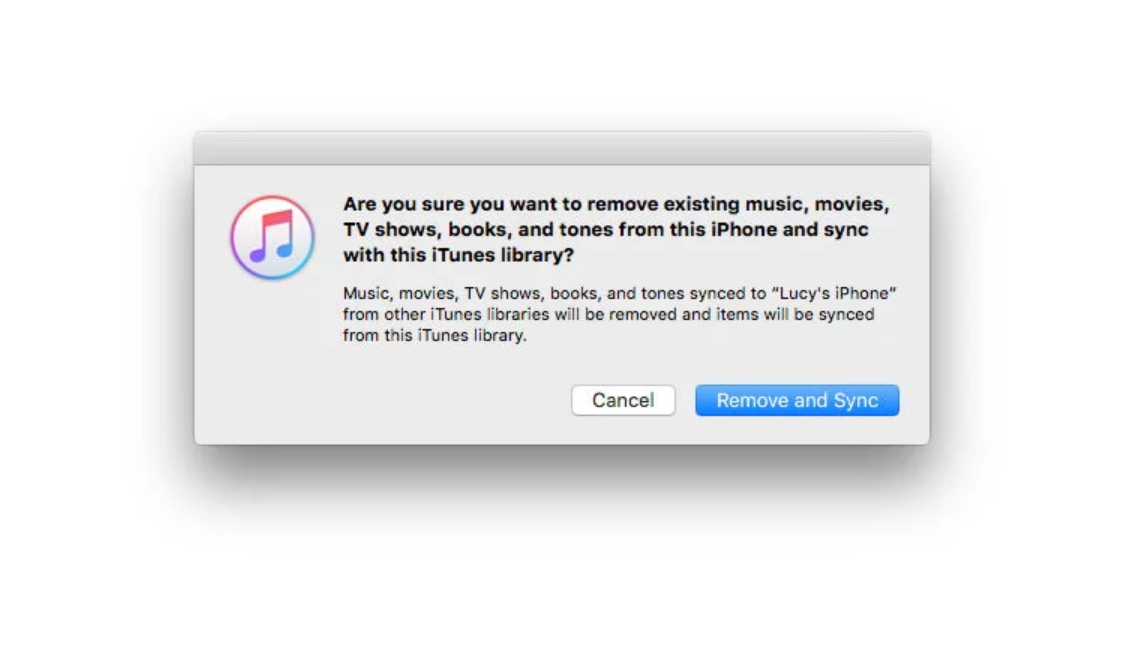

One of my favorite error messages of all time comes from iTunes, the software that will never truly die. If you plug in an iPhone with music synchronized to it, this error appears:

The very long string for this is:

The iPhone (Name) is synced with another iTunes Library on (Computer). Do you want to erase this iPhone and sync with this iTunes Library? An iPhone can be synced with only one iTunes library at a time. Erasing and syncing replaces the contents of this iPhone with the contents of this iTunes library.

The first line of text was enough to make me panic, and not bother reading the rest; You’re going to wipe my iPhone? Please don’t! The second line actually clarifies a little bit that this is about music, but it doesn’t offer up any reassurances it won’t just wipe the entire phone. Worse still, the button says Erase & Sync which is not reassuring.

I’m stumped by this error message every time I’ve encountered it, but it could be vastly simplified:

*Do you want to replace the iTunes library on this phone?* You can only sync an iPhone with one library. Continuing will remove iTunes so you can sync with this computer.

Much clearer, right? But it still feels a bit long. We could push this further, given it’s implied the device can only handle a single library:

Replace iTunes library? Continuing will remove iTunes content from your iPhone so you can sync music from this computer.

As for the buttons: OK and Cancel would suffice with the text re-written, given we aren’t planning anything destructive.

Rachel Mullins has a fantastic article about how to apply these practices to your own app if you’re not able to hire a UX writer. Simple steps and a set of rules about how you talk to users goes a long way!

Bring writers in early

The best thing you can do for your business is bring UX writers in early, as you’re first imaging what your product might look like, to help craft copy that forms a tight knit with your design. The way your products speak to users are what they’ll remember, and getting it right the first time can grow your business in the long haul.

If you ever need help or advice, I’ve worked with lots of products, big and small, and love hearing about the challenges teams face talking to their users. Say hello!